Whitney Museum American Filmmakers launch.

Available on Amazon

Book available on Amazon.

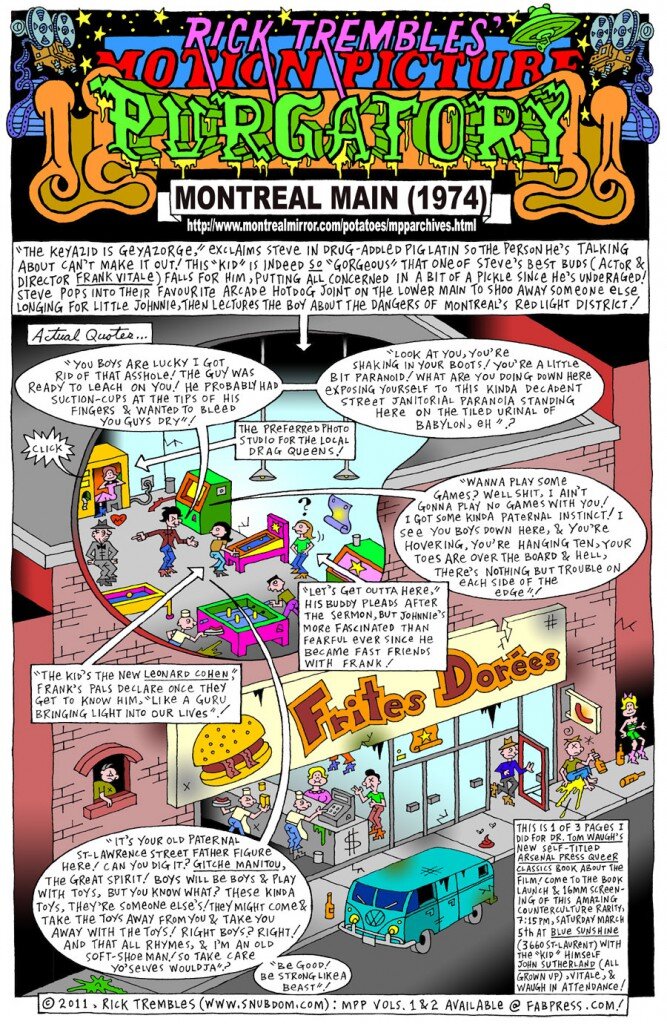

Sample review excerpts for Montreal Main:

"… humorous and surprising. It's a film which above all lives in it people…Afterward, I missed the unique vitality of even the most obnoxious among them." -- Village Voice

"… real, very real. Its reticences are frequently louder than the bald statements of many slicker, more expensive films." -- The New York Post

"… Frank Vitale's Montreal Main is a beautiful illustration of how film can convey nuances of expression, subtleties of personal relationships… It is a work of extraordinary genuineness."

-- Women's Wear Daily

"A raw and perceptive film, one of the most attractive at Locarno and Edinburgh… a humorous and accurate study of a group outside of conventional society."

-- London International Film Festival

"… a movie that ventures into that mercurial threshold of torn and half deserted lifestyles, that explores new regions of scripting and acting, and for those reasons manages to move us deeply, deserves more than commendations or recommendation…" -- Take One

"… bizarre lifestyles are brilliantly etched on the screen." —The Whitney Museum, The New American Filmmaker's Series

"What distinguishes Montreal Main is its uncommon subtleties…" -- Macleans

Montreal Main full reviews: William Kuhns

Take One (Montreal: Vol 4, No 4, 1974), pp.30-31

Early in Montreal Main, the central figure—Frank—pulls his lamentable VW van to a corner and solicits Bozo, as if they didn't know one another. "Hey, hey, let's go for a ride, eh?" They drive for a while, hardly speak, park. Stiff, mercilessly self-conscious, but determined, they stare forward and touch hands. "Do you feel anything?" "I feel... uh... uh... ridiculous." They decide to touch more than hands. We see them sitting in the front seat of the van, two alien figures bent on some add sad task, driven by no more momentum than Bozo's coarse glib fantasy, "The rush of what it feels like to be a homo for an hour."

In its crassness and its tangibly preposterous play-acting, the incident balances and offsets the rest of Montreal Main, which depicts Frank's gentle affection for Johnny, a thirteen-year-old boy from the suburbs. Frank is inarticulate, soft-edged, an artist plagued by his own inertia (sarcastically, Johnny's mother calls him "the noisy silent type"). Johnny is a creature who reminds us of some distant forgotten stage of innocence blurred now by memories of torment; his expressions wavering, incomplete, un-certain. Their first time together they go to a park; Frank photographs Johnny; together they construct a rampart of stick and set it aflame—to step back and hurl rocks and chunks of earth at it, destroying the fire.

Destruction is the inevitable course of every character in the film but Frank or Johnny. There is—in particular—Bozo, the impressario of scorn: he's deserted his own instincts and can only feed off other peoples', usually by pressing them into acknowledging his bilious vision of just about everything. He pummels his girlfriend of three days into admitting that someday the affair will end; and when—of course—shortly afterwards it does, he blames her for being obtuse: "Look it up in the goddamn encyclopedia. Find out what's happening in the emotional lives around you." He's frightening: a perverse Freud with a laser insight into everyone's vulnerability but his own.

Montreal Main is a film of intimate and sometimes devastating characterizations. It maintains a risky course between domestic documentary (I could never quite shrug off the feeling that the film is autobiographical for almost all of the characters involved) and scripted cinéma-vérité. The actors take their own names into the film, and sometimes (as with Johnny's parents) their own real roles; but writer-actor-director Frank Vitale has succeeded in doing something more—considerably more—than to take advantage of filmed psychodrama. Because for all its ambling, casual structure, and its strangely coerced dialogue, Montreal Main works as good drama should work: it involves us, makes us care, makes us suffer.

Montreal Main succeeds best where it risks most. One of the risks was language. The final script—which was followed with almost dogmatic accord—had been compiled, I'm told, partly on the basis of early video improvisations, partly from actual tapes of Vitale's friends, including some of the people who would later act in the film. Scripting lines from earlier improvisations and recorded talk is a treacherous venture at best; and Montreal Main lacks both the controlled subtlety of a crafted script and the edgy nuances of fresh, good improvisation. Indeed, much of the dialogue has a stilted, forced, introspective ring reminiscent of // amateur psychologizing, and often we're uncomfortable with the lines and sense that the actors were uncomfortable with them. But perhaps, because the script is a distortion banked so precisely against the distortion of the characters-as-them-selves, it works. To hear people speak words that their friends (or they themselves) might have spoken once in earnest has an eerie, beguiling authenticity to it, and makes us conscious that we're not looking at characters, but at roles; just as the actors seem so often vividly, visibly self-conscious of playing roles. This isn't to denigrate the acting in Montreal Main, but to suggest its unusual, fervid pitch. It's a distinctive kind of acting, tight but casual, with none of the playful smugness of the Paul Morissey films, nor the pained embarrassed silences of most vérité films; indeed, Vitale and his players have worked out an acting style that be-comes all the more convincing because we can see that it is strained, and all the more compelling because the actors don't make enormous efforts to mean what they say.

But Montreal Main (will this be the line clipped for reprinting?) will probably be a box-office disaster. At least now. It's too rough-edged, too shaggy, too reminiscent its surfaces of that horde of experimental ventures that didn't work. No matter that Eric Bloch's color cinematography is controlled, intelligent, and often superbly revealing; no matter that the editing, despite its spurious feel, has a marvellous tempo that never goes glib and only rarely seeks out effects; no matter that there are moments of distinctive and incredible humour, touching pathos, absolutely stilling lyric sadness; no matter that the film was shot for less than $20,000 against insufferable odds; no matter that it's the most sensitive and honest depiction of homosexuality—or its origins—that I've ever seen in a film; no matter that it's a frail masterpiece and emotionally the most powerful English-speaking film made to my knowledge in Canada; no matter.

If there is a distinctly new sensibility that will emerge in movies over the next six or eight years—and for the movies' sake, there had better be one—Montreal Main gives us a hint of what it might be like. Montreal Main is a primitive work, and like many primitive works will probably be best known as an archeological phenomenon: that is, it will be seen far more often in the future —after Frank Vitale has become a "name" director (which, on the evidence of this film, appears incontrovertible)—than now. Any movie that can touch our feelings, move us to an emotional point that we've never visited before, deserves to be commended and recommended. But a movie that ventures into that mercurial threshold of torn and half-deserted lifestyles, that explores new regions of scripting and acting, and for those reasons manages to move us deeply, deserves more than commendation or recommendation or this review. It deserves to be seen by every director and producer and writer and actor in the industry, to show them what they're facing (or what they dread to face): which is the problem of finding a way to deal convincingly with the trauma of what our lives are becoming.

—William Kuhns

Uncertain Identities

a discussion of

Montreal Main (1974)

—Peter Harcourt

Chaque homme doit inventer son chemin.

—Jean-Paul Sartre

In the 1960s, during the incipient years of the classic Canadian cinema, filmmaking was a cottage industry. Even at the National Film Board, the nation's only source of continuous production throughout the 1950s, filmmakers worked at the level of craft. Although series such as "Faces of Canada" (1952-53) and "Candid Eye" (1958-59) were designed specifically for television, many films were made in more speculative ways. Corral (1954), City of Gold (1957), and Lonely Boy (1962) all sprang from the passions of individual filmmakers, creating a reflective documentary that is virtually without equal anywhere in the world.

In the early 1960s, films grew out of personal enthusiasms. Canadians wanted to make movies about their owns lives and they wanted to make feature films. At the Film Board, both Le Chat dans le sac (1964) and Nobody Waved Goodbye (1964) emerged from intended shorts; while outside the Board, films such as Seul ou avec d'autres (1962), The Bitter Ash (1963), À tout prendre (1963) and Winter Kept Us Warm (1965) were stitched together from whatever scraps of financing the filmmakers could assemble.

The establishment of the Canadian Film Development Corporation in 1968 raised the production of films to a more professional level: filmmakers could now be paid! But since the CFDC had no mandate for distribution or exhibition, the films were rarely projected. This situation led to what I have called our Invisible Cinema—films which existed but were seldom seen. Nevertheless, films such as Valérie(1969), A Married Couple (1969), Il ne faut pas mourir pour ça (1969), Goin' Down the Road (1970), The Only Thing You Know (1971), Mon Oncle Antoine(1971), The Rowdyman (1972) and Paperback Hero(1973) began to define a classic Canadian cinema.

These were the days of cultural idealism. With little reflection concerning race or gender bias, this concern with what kind of film would be truly Canadian inflected the cultural attitudes of the time. Indeed, the nationalist enthusiasms of the 1970s even led me to describe The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz (1974), somewhat mischievously, as the best American film made in Canada that year! And, indeed, the film did suggest a template for later films to come.

Nowadays, many American films are made in Canada and an even greater number of Americanized television programs. In 1984 when the CFDC morphed into Telefilm Canada, film production became not only more professional but also more industrial. Careers were now possible within film—not just avocations. And from this industry, substantial figures have emerged—David Cronenberg, Denys Arcand, Léa Pool, Atom Egoyan, Jean-Claude Lauzon, William D. MacGillivray, Patricia Rozema and many others.

And yet, in spite of inflationary funding policies, there is still an underground Canadian cinema—little films made on small budgets out of individual passions, in English Canada often outside the major production centres. For example in 2000, Red Deer appeared from the prairies, Parsley Days from the Maritimes and La Moitié gauche du frigo from Quebec. These films have received limited exposure, carrying on the tradition of a distinguished but invisible cinema—an artisan cinema always searching for self-definition.

I offer this synoptic preface because in 1974, Montreal Main grew out of this cottage industry tradition. With a grant of $17,000 from the CFDC at a time when Canadian features were costing about $250,000, Montreal Main was shot on 16mm for $20,000. Conceived by Frank Vitale but collectively directed, scripted and enacted, the film takes us into areas where we had never been before and where, to this day, some of us may not wish to go. Furthermore, as in the foundation films of the 1960s as if to valorize their true-to-life dimension, the names of the characters retain the names of the actors.

Montreal Main explores the growing friendship between Frank (Vitale), in his late twenties, and Johnny (Sutherland), a twelve-year-old boy. This friendship comes increasingly to trouble Johnny's liberal but conventional parents, Ann and Dave (Sutherland). It even troubles the gay community on the Main where Frank hangs out. A parallel story explores the troubled courtship between Bozo (Allan Moyle), Frank's best friend, and Jackie (Holden)—a young woman visiting the Sutherlands.

These intertwining narratives gravitate around two opposing worlds, two competitive philosophical attitudes. The existentialist position represented by Bozo and his gay friends, Stephen (Lack) and Peter (Brawley), doesn't assume it knows the emotional priorities of existence. These characters discover their emotions through experience, by acting out different roles—in Bozo's case, often with sadistic insistence.

The essentialist position, on the other hand, represented by Jackie and the Sutherlands, assumes that the emotional priorities of human nature are a given. One simply has to mature into them. Caught between these life assumptions are both Johnny and Frank—Johnny because, at twelve years of age, he is not yet an independent agent, and Frank, because he is so afraid of who he is and of what he might become. These two attitudes are cross-cut throughout the film, often with ironic effect.

The film opens with a sense of personal relationships as a battle ground. As the camera moves in on the outside of Frank's loft on St. Lawrence Boulevard—the Montreal Main of the title—we hear Frank and Pammy (Marchant), shouting at one another. He is trying to get her to leave. When we move inside, we see Frank exchanging money with someone (does it concern drugs?) because we recognize that Pammy is a distressed junkie—obviously into the hard stuff. Pammy represents a limit beyond which Frank wont go. He wants her out.

This scene is followed by Ann Sutherland on the telephone, her groceries on the counter, as if to suggest that each group has its preferred means of communication and its need for a particular kind of supplies. Similarly, when in a later scene we watch Peter and Stephen making up as queens, dressing up for a night out on the Main; in a previous one we had seen the Sutherlands getting ready for their party—dressing down by washing and grooming and by Ann shaving her legs.

The Sullivan party brings about the encounter between Frank and Johnny. Bozo is having a good time, coming on to Jackie; but Frank is gloomy and alone, wanting to go home. When he drifts upstairs simply to look around, he peers through a door to see a creature with long hair reading about Call Girls in a magazine. Is this creature a girl or a boy? Frank dons an African mask that is hanging nearby and approaches from behind. When Johnny looks around, their eventual encounter startles them both as it startles spectators. Silent close-ups abruptly end the scene.

Since all their friends are gay, Frank and Bozo feel that they too should be gay; but their attempts to be gay with one another lead only to embarrassment. During a night scene in Frank's beat-up Volkswagen van when they are trying, unsuccessfully, to masturbate one another, there is a decontextualized cut-away to Bozo talking about Frank: "What he'd really like," Bozo declares, "is the rush of what it must be like to be a homo for an hour." With Bozo, apparently, nothing is serious. With Frank, on the other hand, everything is.

Because Frank is a photographer, he arranges to take Johnny up on the mountain for a photographic session. In the style of the 1970s, Johnny is very feminine. With his long hair and gaunt face, he looks more like his mother than his father.

Up on the mountain with Frank, at first Johnny is shy—resistant to the camera. But they start to play games. They build a citadel of wooden matches—in this as in later scenes literally playing with fire. They then spin coins in a café and generally, hang out together, becoming friends. The scene ends with Frank and his camera again, the film's camera moving in on a BCU of Johnny's face, this time relaxed by the acceptance of trust.

Whatever one's value system, this extended scene between Frank and Johnny depicts a beautiful exploration of a friendship. The nuances between them are delicately handled and for non-professional actors, the performances are extraordinary. If the relationship between Frank and Johnny provides the moral centre of the film, the ethical centre could be located in three pivotal scenes between Jackie and Bozo.

The first occurs in a department store. The two of them are still close, as they kibitz about amongst the consumer goods. He wants to buy her something silly, like the lapel flowers they exchange later on. She wants to know how long they will be together. He wants to play, she wants to be serious. As elsewhere in the film, Bozo favours the improvisational, Jackie the predictable. At this stage, the way spectators react to these issues will affect the way they react to the characters.

The second scene occurs in a shopping mall. Stephen has been baiting Jackie in a way she doesn't understand. She stomps off and Bozo runs after her. He tries to persuade her that they were just having fun. Jackie still feels humiliated and annoyed.

The third scene takes place on a wintry roof top. There is now indeed a chill in the air. "You're a big joke, Jackie," he shouts at her. "You're like the Sullivans—all hip on the outside , scared and nervous on the inside." She in turn can no longer stand what she calls "his supercilious smirk," and he can't stand the "high-pitched righteous tone" she thrusts at him. The scene ends with Bozo screaming that she will never understand "what's happening in the emotional lives around you."

By this stage in the film, Bozo is not likable. His improvisational style perpetually migrates into a personalized theatre of cruelty. He can be as hurtful with Frank as he was with a couple of teenage girls in the van that he set out to humiliate. He is, indeed, as Bill Kuhns once observed, an "impresario of scorn."

Nevertheless, what he says to Jackie strikes home. Hurtful in intent, his comments register an integrity—at least to his own feelings. Jackie, on the other hand, might seem to be living in a classic Sartrian way in "bad faith," in emotional inauthenticity. Whether or not we like the way they occur, Bozo's accusations are hard to dismiss.

Full of equivocal relationships, Montreal Main constructs a world of moral ambivalence. On one level, it is a love story, exploring, as Natalie Edwards wrote at the time, " the diversity of sexuality, the shades and shifts lying inherent and unacknowledged in all people." On another level, it extends outwards towards allegory—towards a philosophical investigation of the world. Fragmented in style, swish-panning its way from close-up to close-up, Erich Bloch's camerawork creates a sense of hysterical excitement. Re-enforcing the improvisational nature of the action, the grab-shot technique suggests a world in which attention is uncertain and perception unclear. Lacking parsable narrative sequences, the style perfectly parallels the feelings of isolation that a clutch of gays might have felt at the time in a straight world or that anglophones might have felt within a culture that was becoming insistently francophone.

Even the rap patter of Stephen Lack suggests a world in which words have lost their social efficacy; and the uncertain sexual preferences of Bozo and Frank might convey the sense of an existential terror—especially for Frank. Unlike Bozo who, in his opportunistic way, preys upon whatever happens to be around, Frank is a timid idealist, always looking for something different from his day-to-day life, perhaps something impossible—like an intimacy with Johnny. He is frightened by loneliness—a fear re-enforced by the many cut-aways in this film to aging faces in isolation, suggesting the desolation of unattached old age.

If the film begins with domestic violence between Frank and Pammy, towards the end we have two additional scenes of violence intercut with one another. Frank and Bozo have an angry quarrel in a deli, while Dave and Johnny have one in the car—both of these scenes suggesting the hurtful undertow of an unrealizable love.

Having been discouraged by his friends and forbidden by Dave, Frank agrees to stop seeing Johnny. But Johnny is more courageous. He slips away and visits Frank's loft, declaring he wants to live there. They go for a walk and, when Frank sends Johnny into a restaurant to buy cokes, Frank abandons him.

The scene ends with Johnny running through the streets and back lots of east-end Montreal, at one point dropping the bottles of coke while the music of Beverly Glenn-Copeland, as it had once before, moralizes the theme of the film—even acknowledging its gender uncertainty:

And up and up the streets we roam,

We are lookin', growin' and a-lookin',

And up and up the hills we run,

We are lookin', climbin' and a-lookin'

For something to get us there,

Anywhere …

Brother, Sister—

Who do you think you are?

The film itself ends with Bozo comforting Frank and then with a return to a games arcade. It is full of old men who also are a-lookin', without comprehension, at nothing at all. The camera then picks up Johnny, also by himself, shooting away his hurt at electronic targets, his future uncertain.

Montreal Main is an extraordinary film. Naturalistic in appearance, it has the air of making itself up as it goes along. Yet every image in the film and every element of its style possess the resonance of metaphor. Everything is what it is and yet, like the classic Film Board documentaries of the 1950s, suggests other things.

A "shooting star" within English-Canadian production in Montreal at that time, as Michel Euvrard has described it, appearing "with neither ancestors nor progeny," made by actual people at least in part about the realities of their lives, finally Montreal Main enacts a philosophy of uncertainty. Within this uncertainty, Frank yearns for the consolations of a forbidden love. He doesn't want to become one of the old men in the arcade. What Johnny offered him was unquestioning trust. Not certain himself whether his love for Johnny was erotic or big brotherly, Frank had to betray that trust. The relationship was not to be.

The film confirms the uncertainty that most of the characters feel and that Jackie and the Sutherlands are too afraid to acknowledge. As the credits roll, Beverly Glenn-Copeland sings out again her final refrain:

Brother, Sister—

Who do you think you are?

ON FRANK VITALE’S MONTREAL MAIN By John Greyson

Curatorial essay by John Greyson to accompany The Cinema Lounge screening of Frank Vitale’s

Montreal Main on Oct. 25 / 09

Montreal Main, hereafter referred to as M&M, is many things: a museum of anglo Montreal bohemian manners; an extended commercial for Swartzes Deli; a love-letter to the loft-dwellers of St. Laurent's schmata stroll; a catalogue of latter-day neo-realist indie cinema techniques and clichés; a time capsule of early seventies hair styles; a love triangle between two 27- year old straight guys and a 12-year old boy named Johnny. M&M is many things – but first, some things that it is not.

M&M is not Easy Rider (released that same year, in 1974): Instead of throbbing choppers, there is a battery-impaired VW van. Instead of butch existential Dennis Hopper, there is fey talkaholic Stephen Lack. The two films share the narcissism that typifies many collectively produced buddy movies: scripts written and improvised by the actors, who together shared the credits; meandering plots that are as keen to explore the rabbit holes as they are to stick to the main road; directors (Dennis Hopper, Frank Vitale), both confident enough and self-indulgent enough to cast themselves as their own stars. M&M's central team of Vitale/Moyle/Lack may share the boys-will-be-boys hubristic drive to 'make a movie' at any cost that binds them to Fonda/Hopper/Nicholson, but the result is odder, sweeter, kinder... and memorably more anti-climactic. M&M is not an Abercrombie & Fitch/Larry Clark/Bruce Weber fantasy, trafficking in acres of tanned adolescent flesh in order to sell us acres of plaid adolescent boxers. Clark, Weber and Abercrombie all may variously oppose the moralistic 'save our kids' hysteria that permeates mainstream western culture, but in their varied efforts to display the 'reality' of teen sexuality, they can fall all too easily into a predictable and pretentious voyeurism that seems to 'pimp our kids' as a coy alternative. Despite the best efforts of Harmony Korrine, Clark can't seem to help himself or his camera from the disappointing limits of reductive scopophilia.

M&M is not Les Ordres, Michel Brault's great verite melodrama, also from 1974. Montreal was in the full-throttle grip of it's own Quebecois nouvelle vague, with features by Arcand, Lefebvre, Groulx and Heroux being produced inside and outside the NFB's venerable head office. The stories they told, in the me-generation aftermath of the FLQ crisis and Expo 68, were equal parts social critique and domestic commentary, and like M&M, these often embraced the low-budget doc-inspired verities of available light, handheld camera work, improvisational naturalism, and an inspiring disregard for location permits. Les Ordres features an ensemble of characters drawn from life and rigourously engaged in their political moment, whereas M&M just as rigourously refuses to reference political struggles of any description that were then playing out on Montreal's streets: fights around language laws, the anti-poverty activism of the time, native and immigrant rights, or the early efforts of a fledgling gay rights movement. Instead, M&M's hints at the social and the engaged are fleeting glimpses, scraps and gestures, not full-blown narrative engagements.

M&M is not the South Park episode where Cartman is counselled by his shrink to join NAMBLA – the North American Marlon Brando Look- Alike Association. Cartman gets his acronyms confused and instead hooks up with NAMBLA, the North American Man Boy Love Association. Much deliciously tasteless mayhem ensues, with the Brando-lookalikes eventually teaming up with the FBI to raid the annual boylovers banquet, where an oblivious Cartman is guest of honour. M&M was shot in 1972, 5 years before Anita Bryant launched her 'Save Our Children' campaign, 7 years before Toronto's radical Gay Liberation newspaper The Body Politic was busted on trumped up charges of distributing child pornography (it took 3 trials to get the case dismissed), 9 years before North America's gay movement was gripped by rabid NAMBLA-baiting, with the Christian right inventing kiddie porn scandals and child sex rings, which would convulse opportunistic police departments and tabloid newspaper headlines for decades to come. M&M was made in a post-sixties bubble of semi-innocent uncertainty, where both children and adults had rejected rigid fifties definitions of youth sexuality and embraced the concept of childrens rights, along with civil, womens and gay rights, but still had no definitive language for what this might mean.

M&M is not Il Etait une fois dans l'est, (Once Upon a Time in the East), a big-budget queer Quebec epic (also 1974), with a script by Michel Tremblay and directed by theatre legend Andre Brassard. This ambitious ensemble work by two of Quebec's most celebrated queer artists focuses on the francophone drag sub-culture of St. Catherine and the Cleopatra, where Tremblay's play Hosanna was set. A prestige project that debuted at the Cannes Festival, it built on the extraordinary tradition of Quebecois queer cinema launched by Claude Jutra's precocious 1964 A Tout Prendre, and anticipated the many dazzling Francophone queer features that were to follow: Being at Home with Claude, The Orphan Muses, Crazy, and this years I Killed My Mother. Montreal Main was another beast altogether, bemused and seemingly out on its own idiosyncratic limb, made by two bi-curious anglo best friends, their noses pressed to the glass of Montreal's gay demi-monde, content to steam the glass but not venture within.

M&M is not Death in Venice, Visconti's 1971 masterpiece which Frank Vitale and co-star/co-writer Alan 'Bozo' Moyle must have seen. This languid, opulent period piece is the anti-thesis of M&M's resolutely gritty neo-realism, (tho Death displays a telling weakness for seventies signature zoom-lens shots). Death is perhaps the ur-text for all the varied man-teen or man-boy love efforts that were to follow, (despite the best efforts of Anita Bryant and co), many of them as low-budget and neo-realist as M&M: Artie Bressan's brave if schematic Abuse, about a gay photographer who falls head over heels for a boy suffering from brutal physical abuse at the hands of his parents; Keanu and River, gay-for-pay as Portland teen hustlers in Gus Van Sants' glorious My Own Private Idaho; For An Unknown Soldier, depicting the treacly affair of a Canadian solider in World War 2 and a 14-year-old; The Blossoming of Maximos Oliveros, Auraeus Solito's stunning debut about 12-year-old Manila sissy who falls for a kindly butch cop; L.I.E., a study of two teen petty thieves who get involved with a menacing Long Island pedo, played majestically by Brian Cox; Mysterious Skin, Gregg Araki's haunting mood piece about two more teen delinquents who cope with childhood molestation traumas by confronting memories of alien abduction; Amnon Buchbinder's Whole New Thing, a touching comedy about a precocious queer teen and his nervous closeted teacher, played by the great Daniel McIvor; and most recently, Shank, about a bunch of queer-bashing Bristol hoodlums and their relationship with another queerish high school teacher. What they share across these 35 years is an insistence on the specificity, and dignity, of their varied protagonists.

M&M is not many things, and it is many things. It is a film that was first shot completely on video as a test-drive, using equipment from the Montreal co-op Videographe, with the crew for the video shoot being bigger than the crew for the eventual film. The film version was shot for $2000 cash, investment from a friend – and then a rough-cut screening for the Canadian Film Development Corporation resulted in an extra $17,000 to finish, mix and blow M&M up to 35mm (Vitale claims half of this was spent on the music.) It started as an autobiographical portrait of the friendship between the two main collaborators Vitale and Moyle, and then evolved into a what-if triangle involving a 12-year-old boy, with the film becoming a public site for Frank and Bozo to perform their confused sexual and emotional tensions in front of the camera.

M&M is many memorable things, and here are some of the ones to watch out for:

1. Count the number of times they say 'eh' in the film. It's a lot. Especially Stephen Lack, a queerish Jewish artist whose accent cross-Atlantically wanders from Dublin to St. Johns and back, (sometimes in the course of a single sentence) and who has gone on to a career as an acclaimed painter in New York. (Trivia: in the late-seventies, he was dating a precocious Stephen Andrews, a Toronto artist and my current partner, who has excellent gossip about him).

2. Count the number of French words spoken in the film. It's about a dozen, and 'frites' is more than half of them. M&M is utterly unselfconscious about the unbridgeable divide it portrays between the French and English cultures of 1974, two distinct worlds, with St. Laurent (the 'Main') becoming a red-lit Berlin Wall dividing English west from French east.

3. In his voice-over commentary on the newly released DVD, Vitale remains as sincerely heart-on-sleeve and as genuinely confused as the 'Frankie' he portrays is in the movie, unsure of what he thinks, feels or desires for Johnny or Bozo. Significantly, everyone in the film uses their real names, and the blur beyond dramatic invention and documentary observation purposely and continually collapses. During the making of the film, the long-standing bromance of Frankie and Bozo seems to suffer sustained damage. Vitale went on to direct another feature, East End Hustle, and today makes industrials, commercials and documentaries. His evident pride in M&M remains rightly undiminished.

2. Moyle indulgently portrays himself as a self-absorbed sadistic misogynist, revelling in his eruptions of alternating fondness and nasty teasing with Frank, his girlfriend, and the others in the crowd. He went on to a significant Canadian/Hollywood career with The Rubber Gun, another instant classic of early seventies Montreal anglo cinema; Times Square, Pump Up the Volume, New Waterford Girl and Man in the Mirror (The Michael Jackson bio-pic). We co-taught a production workshop in Ottawa together a decade ago, and he was as saucy, sharp and endearing as the Bozo he plays on screen. As an exercise, he had to block an unrehearsed scene with two actors in front of an auditorium of workshop participants. The scene was from Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf, and while watching M&M, I found myself imagining him in the Liz Taylor role, screaming "an assistant professors salary!" in the manner of the M&M 'You Scum" line. Watch for it, and think Liz – I don't think I'm wrong.

3. Johnny Sutherland was the 12-year-old dues ex machina cast to break up the bromance, and he and his parents and their NDG house all play themselves. It's a scenario that's hard to imagine today: a middle-class vaguely bohemian family, recruited by this strange bi-curious duo from the Main with a budget of $2000, to star as themselves in a melodrama about man-boy desire. To their infinite credit, all three Sutherlands give compelling and understated performances, and Johnny is nothing short of a revelation, holding the screen with a fawn-like calm that is as mesmerizing in its own way as Bjorn Andrésen's rendition of Tadzio in Death in Venice. Shortly afterwards, Johnny's folks split up and Johnny went to live in Europe, where he became a champion downhill skier and later, a Canadian speed bike racer. Now 49 and speaking on the DVD's commentary track, he's as guileless, sweet and unfazed today as he was in the film at age 12, when he astonished viewers with the poise of his performance.

4. Beverley Glen Copeland, M&M's composer and singer, created a score of distinctive original songs for the entire film, in the manner of Aimee Mann's (almost) solo turn as the musical voice of Magnolia. Copeland anticipates the velvety vocal ache and queer urgency of Joan Armatrading and Tracy Chapman, though without the breakout success that these two enjoyed. Instead, Copeland has transitioned and is now living as a man named Phynix, still recording and performing in Montreal, the voice still as mesmerizing as ever, well into his sixties. As film scholar Tom Waugh notes on the commentary track, his/her voice and musical style would have been perfect to do a cover of the standard 'Frankie and Johnny were lovers', a camp gesture that is perhaps still possible as an extra on a future DVD release.

Waugh argues that M&M remains one of the most compelling and haunting debuts in the history of Canadian cinema, a landmark of early seventies verité, a ground-breaker of global queer cinema, and a quirky, unique portrait of a more innocent time. The very inconclusiveness of the gentle ending is a telling transgression of gay 70s cinematic narrative traditions, which all too often insisted on the violent death of the queer tragic hero. Instead, M&M represents the sort of story-telling that we all need to be reminded of: questioning, nuanced, unresolved and deeply human, one where all three sides of this triangle are allowed to walk away, and to wonder.

Background on John Greyson

John Greyson is a Toronto film/video artist whose shorts, features and installations include: Fig Trees (2009, Best Documentary Teddy, Berlin FIlm Festival; Best Canadian Feature, Inside Out Festival); Proteus (2003, Best FIlm, Diversity Award, Barcelona Film Festival; Best Actor, Sithenghi Film Festival); The Law of Enclosures (2000, Best Actor Genie); Lilies (1996 - Best Film Genie, Best Film at festivals in Montreal, Johannesburg, Los Angeles, San Francisco); An associate professor in film production at York University, he was awarded the Toronto Arts Award for Film/Video, 2000, and the Bell Canada Video Art Award in 2007.

Cinema Canada 15, August/September 1974, pp.78-79

Frank Vitale's remarkable first feature film, Montreal Main, probes deeply into the troubled and insecure inner core of the people who will not conform to society's limiting black-or-white, male-or-female classification. And in so doing it suggests the diversity of sexuality, the shades and shifts lying inherent and unacknowledged in all people. Watching, you flash Lolita, Peter Lorre as "M", parental incest, and a flood of forgotten allusions from history and literature about the secret mysterious world of indeterminate sex and forbidden love.

Long after sexual diversity is acknowledged and understood, Canadians will be proud of this early work, this original, brave, revealing and beautifully constructed film.

It has the integrity of a diary, or a confession. It is an inside study of humans hunting for those relationships that define emotional life. In a world where sexuality is no longer linked inevitably to parenthood, and people are becoming disconnected digits in a computerized society, desperate for individual meaning, the relevance of the need to love and be loved, and perhaps the impossibility, have implications that reverberate into the twenty-first century.

With zero population, and the next generation about to become the first so-called "permanent society" the male and female will obviously develop into other beings than those their genders define now as essential to the survival of the species. Vitale's film previews a world where the only real need the characters have for each other is the need to be needed. During the course of the film the consequences of that and the resulting emptiness make us realize that in losing adherence to animal functions and their structures (hunting, bearing, protecting, helping each other survive) we drift into a realm where individual purpose is lost and emotional survival endangered.

Thus a grimy group of Montreal Main's loft-dwellers, artists and gays, and their incestuous infatuations, jealousies and experiments, offer not only a widening experience for an audience, but a portent of a future generation's problem in finding out how to be needed as individuals, when no one is.

Credits for script and cast are the same. Following studio, star and auteur systems in filmmaking, group or cooperative works are now developing a new strength and popularity. Vitale's work is a forerunner here also. A kind of Imaginary Documentary, he and his friends have found a way to present what amounts to a conjecture, or daydream, in the style of reality.

Charged with a raw realism created by the semi-improvisational technique, it hoodwinks the audience into forgetting this is no Actuality Drama, à la Allan King, but an exploration of possibilities that, like daydreaming, permits safe investigation without actual danger. Perhaps it is Vitale's way of clarifying his thinking, looking for solutions, diverting his energies and avoiding mistakes; indeed, living a projection of his life based on truth: an Imaginary or Pretend Documentary.

At any rate, it works and works well. Vitale is one hell of a filmmaker. His background includes Country Music Montreal 1971, a competent and original study, shown on the CBC; being associate-director and co-producer on some four or five films during the time he lived in New York; and experience as unit director on Joe and as a cameraman for Newsreel.

Vitale's editing is often superb; intuitive and exciting. The style of the film encompasses lyricism, impressionism, routine shots and awkward, jumbled, hand-held shooting, in a combination that at first seems jarring until one realizes that it simply mirrors the way we see life: things are beautiful sometimes, ugly another. The technique, style and theme blend inseparably and Eric Block's camerawork is totally unified with Vitale's direction.

Unfortunately improvisational acting techniques seem to have caused almost impossible sound problems for Pedro Novak, and many words, phrases and comments are muddied, missed and lost. This is too bad particularly because on a first viewing you need all those words to help keep everyone sorted out and the plot figured, since the film doesn't follow precise chronological or linear action.

The music is aptly composed by jazz improvisational artist Beverly GlennCopeland and is fittingly lyrical on the surface, nervously pulsing underneath, underlining and in harmony with the film.

Finally, the story: The main plot involves a bearded photographer named Frank, played by Frank Vitale, and his many-leveled and complicated infatuation with a twelve-year-old boy named Johnny. Whether motivated by beauty, jealousy, longing for youth, innocence, mystery or rebellious defiance of ethical codes, the friendship between the two includes attractions of parenthood, brotherhood, sexual love, danger and perversity. The theme is reversed and carried into a sub-plot involving Frank's friend Bozo and his attempt at a love affair with a charming, normal girl named Jackie.

Both expose the ignorance of the straight world about other emotional worlds, the radiating consequences of love and lovelessness, and the limitations of a system that believes the myth that gays are witty, supercilious fun-people, sarcastic and superficial, and that everyone else knows their own sexual self.

This is a subtle, splendid film.

—N.E. [Natalie Edwards]